During the Second Punic War Carthage sought to attack Rome, but had lost her previous naval superiority,

so the obvious route across Sicily was blocked.

Instead their general Hannibal Barca raised an army in Iberia,

marched across the Pyrenees and the Alps and attacked the Romans from the north.

He beat them at the Battle of the Trebia and again at Lake Trasimene.

The Roman Fabius Maximus was oppointed dictator and applied scorched earth tactics against him.

This did not go well with the population of the land, so in 216 BCE the Romans appointed new commanders, who tried to stop him at Cannae.

Knowing Hannibal's skill in battle, the Roman senate brought an unprecedented 8 legions into the field.

However it is unclear if they were at full strength.

Numbers for the Roman side range from about 50,000 to 90,000, mostly infantry and some 6,000 cavalry.

All sources agree that the Romans outnumbered the Carthaginians, who are estimated at 35,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry.

Hannibal's army was a mix of Libyans, Iberians, Gauls, Gaetulians and Numidians.

The Romans had stronger infantry, both in quantity and quality, the Carthaginians likewise in cavalry.

It was Hannibal who took the first step, by seizing a supply depot at Cannae, cutting the Romans off from that important store of supplies.

The Romans then sought and found him at the river Aufidius, yet did not engage immediately.

Hannibal provoked them by sending his cavalry to harass their foragers.

After this, the Romans decided to give battle.

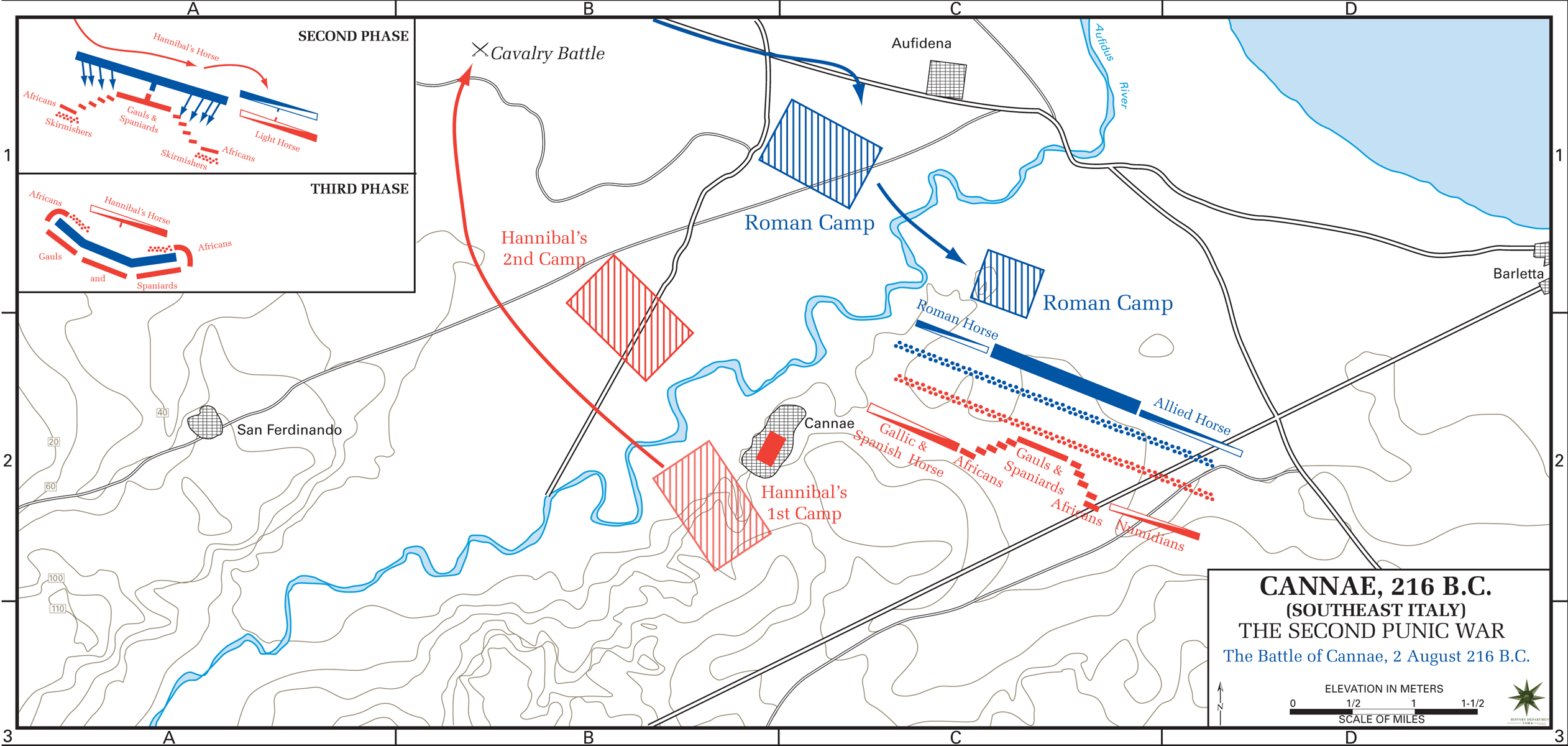

Both sides lined up in the conventional way, infantry in the center and cavalry on the flanks.

The Romans used their numerical advantage to create a deep and heavy center, intending to break the enemy like they had done at Trebia.

Their commander Varro was confident that Hannibal could not employ his usual ambush techniques and because the terrain was open and there was little room for retreat.

Hannibal put his Gauls and Iberians in the center and his veteran African infantry on the flanks.

His brother Hasdrubal led his medium and heavy cavalry on the left and the light Numidian cavalry was stationed on the right.

When the two armies approached each other, Hannibal deliberately held his flanks back, creating a formation that bulged forward.

He had made sure he also had the sun and wind in his back, so that these hindered the enemy.

When the two sides clashed, Hannibal, controlling his troops from the center, had them make a slow fighting retreat,

gradually changing his formation from convex to concave.

This made the Roman formation more and more chaotic, their superiority in numbers lost in the confusion.

In the meanwhile the Carthaginian cavalry on the left flank attacked the Roman riders and drove them back.

The early confrontation caused by the infantry bulge gave them time to finish this task.

Next, they wheeled inwards and attacked the Romans from the rear,

while the African infantry on the flanks also turned, to create a complete encirclement.

The Romans were defeated and butchered until nightfall, when part of the army managed to break out and flee.

Hannibal lost a 6,000 - 8,000 men.

Estimates for the Roman losses range widly, from as little as 10,000 to as much as 60,000.

Most historians estimate that about half the army was killed and many thousands taken prisoner.

The shattering defeat, worse than those at Trebia and Trasimene, threw Rome into despair.

Many cities and tribes in southern Italy and Sicily went over to Hannibal's side.

Depite his success, Hannibal knew that he was not strong enough to take Rome itself and opened peace talks.

But Roman resolve stiffened and they kept on fighting, eventually winning a war of attrition.

War Matrix - Battle of Cannae

Greek Era 330 BCE - 200 BCE, Battles and sieges